Is this article just clickbait or is it good science?

Being able to understand and judge the validity of research from outside your area of expertise is a challenge, but is growing ever more important. Learning to rapidly read and evaluate research was a skill I built throughout my PhD research, and something I am still improving on now in my role as a research software engineer.

During the pandemic, we saw a surge in health-related pseudoscience being shared across platforms; we also saw misinterpreted scientific results and charts reproduced out of context by large news organisations. How can you quickly look at some results and figure out if 1. the snippet about results shared out-of-context in an article is an accurate representation of the results, and 2. if the research the results come from is valid?

This blog post is aimed at non-academics and out-of-practise academics, and is intended as a quick-and-dirty primer at evaluating research that you might find quoted in news articles, websites, or in other media. Instead of being a step-by-step guide to compiling a detailed literature review, it is instead centered around a few key guidelines or ideas to keep in mind. Within these general philosophies, I’ve included some practical how-to guides. I’ve initially taken the approach that you’ve stumbled upon some quoted research and want to know more, but at the end I’ve given you some steps for effective literature searches if you have a specific topic or problem you want to find out more about.

So, you are wondering about how to take the first steps in improving your data literacy and building skills in assessing research results. Great! Realising that this is a challenge that needs work is the first step! It’s ok if it feels a bit overwhelming at first: you can slowly start applying more and more of the principles below to what you read.

1. How important is it for you to not be mistaken?

You do not have the time, energy, or head space to do a full fact-finding deep-dive into every single statistic you hear quoted. When juggling the incredibly overwhelming torrent of data we consume every single day, you will drop some balls: you will unintentionally believe some misleading data or misrepresented study. That’s ok. This first point is about deciding which balls are glass, and can’t be dropped without consequence, and which balls are plastic and will bounce back without harm.

Let’s just get this out of the way at the very start. It’s important for you to address why you are interested in learning more about a topic. Is it something that you just happen to have an interest in, and want to learn more out of curiosity? Or will you use the research to implement changes in your workplace etc. that may affect other people? How much time and effort do you need to put into understanding the area to ensure you are not misunderstanding something?

Let’s say I want to look into a method of effectively teaching people to code that I saw discussed in a glossy tech magazine.

- If I’m only interested in teaching myself to code, there’s little harm in accepting the article at face value and not digging any deeper. I can try out the methods they suggested, and the only downside if it’s not effective, is that I maybe waste some time on an inefficient method.

- If I’m interested in improving the curriculum for a coding course that I teach, the stakes are higher: I need to due my due diligence to ensure the methods discussed are actually effective, and won’t have unforeseen side-effects or consequences for my students.

It’s completely natural and to be expected that you might misinterpret some literature along the way, but it’s also very important that from the outset you have decided how much of an effect a misinterpretation may have.

In some cases, it may be the case that the stakes are too high, and you need to talk to someone with expertise in this area!

2. Read everything with a critical, skeptical, and curious lens

In the world of research, being critical and skeptical of results is not a negative thing. It’s very important to realise that the playing field of research is very different to that of business or other fields. Not only is skepticism expected, it’s welcomed by the research community: research is designed to be continually improved upon and is not a static thing. As a researcher, I would love for my work to be replicated in the future, with additional newly available data, and proved incorrect or incomplete: that means we have learned more about how our universe works!

When reading results presented in a pop-science medium (whether this is in a book, in an article, or on the news etc.), it’s worthwhile to think about the way in which it’s being reported. What is the outlook of those reporting on the results, and are they trustworthy? Are they trying to sell something?

Are there any graphics or plots being shown to back up the results? Have a read through this post “How To Spot Misleading Charts: Review the Message” which gives you a nice checklist of things to look out for when you spot a bar-chart with a compelling message.

How “cagey” are they about the results? Good reporting on research should read as a bit uncertain or cagey: there are no absolute truths in research, and there are always going to be caveats, limitations, and exceptions. Are these discussed or mentioned at all? Or is all the coverage 100% sure and positive? What do you think might be some limitations to the work?

Along with with this skepticism, curiosity is your best friend: it’s great to consider why someone is researching something, how they came to the conclusions they did. Sometimes, the article or blog post you’re reading might give you lots of this information, for example if it’s specifically profiling recent work coming from a specific lab etc., but sometimes it’s lacking in detail. Is it important for you not to be mislead? Is this one of those cases where you want to make changes based on the research? Then it’s time to go to the source! This leads us on to the next point…

3. Where is the research published?

Let’s go down the rabbit hole now and leave the pop-science articles behind. Let’s find out where the research was originally published. Any article worth it’s salt that is reporting on a research finding should link to the original research paper in the journal it’s published in. Research article URLs will include a DOI or digital object identifier. This is like a library tag that is unique to that research article and can be used to find other papers that reference it etc.

When you’ve found the link to the original paper, there are a few quick steps to take before you try reading it:

What is the name of the journal it’s published in? If you Google the journal name followed by “peer review”, do you see results that mention the peer-review process for articles submitted? If you search the journal name followed by “predatory journal” do you turn up any interesting results? Read more about predatory journals here.

When did the research come out? What may have changed since it was published?

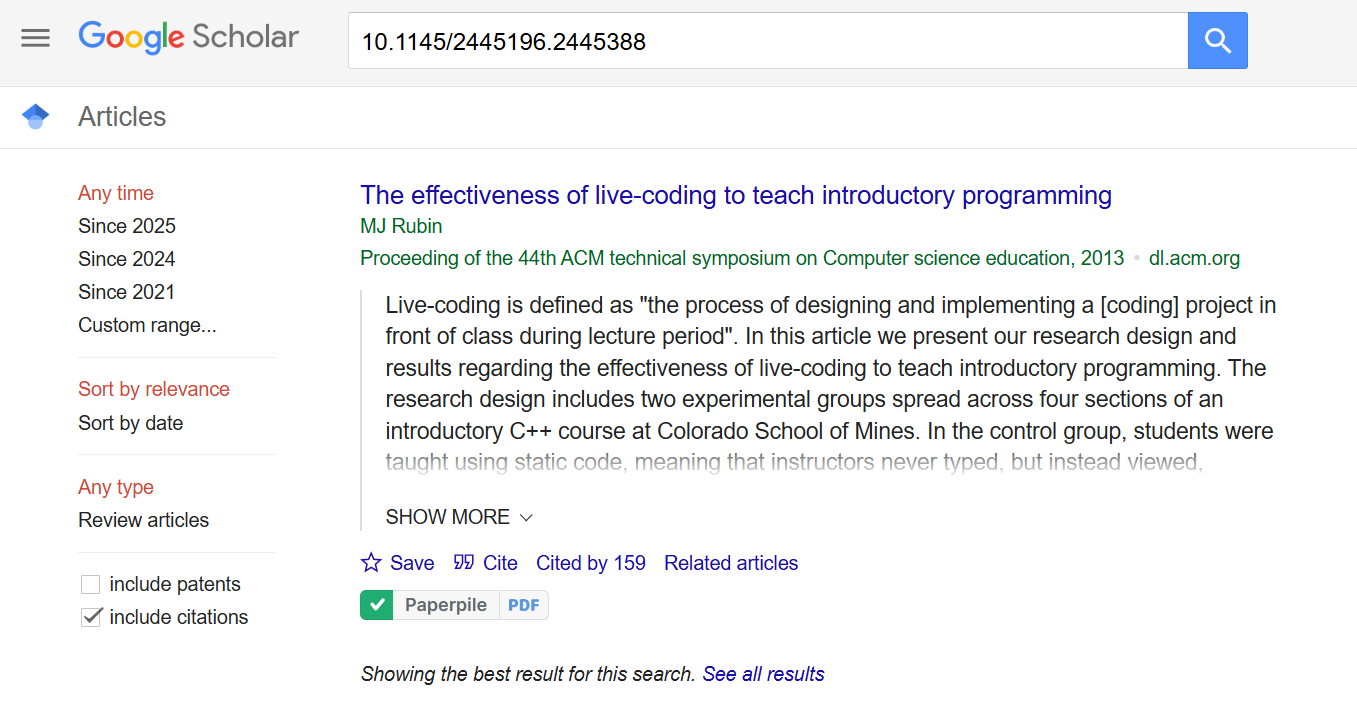

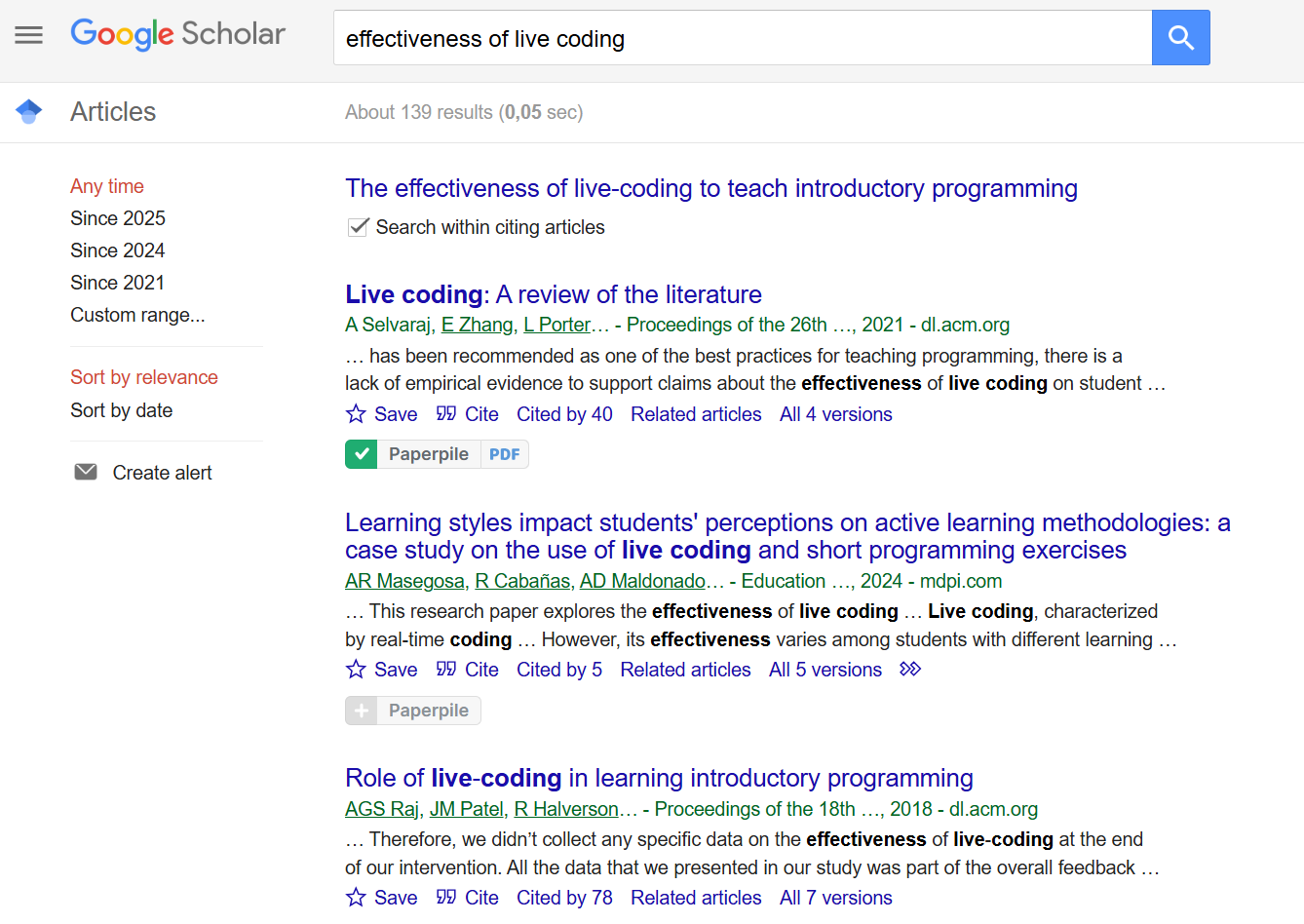

Has anyone cited it? It’s not a red flag if no-one has (if it’s fairly recent, or on something niche), but if there are citations, it’s good to have a look and see what kind of citations they are. You can do this using Google Scholar, and then clicking on the “Cited by” link underneath. You can then check a box to search inside citing articles. I like to search for things like “effectiveness of X” to find phrases in these papers relating to terms. Note that information contrary to the results of the primary paper does not make that initial paper bad: it just means that more work has been done, more information discovered, or more context gained!

At this point, if you find anything called a “review”, “systematic review” - open it in a new tab: this could help you cut down on lots of work later if you really need to dive into the topic!

Ok, you want to actually read the paper? This article, “How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists” by the London School of Economics has a great step-by-step breakdown, and this step-by-step example of reading a real article using this framework shows how to implement these steps.

Research articles and paywalls

You may hit into a paywall when you click through to a specific paper. Don’t fear, there are ways around this.

You can still read the abstract, see the journal the results were published in, who the authors are and where they work, what other works they reference, what works referenced them: that’s an awful lot of information to work with to begin with!

Researchers frequently put PDF copies of their papers on their personal/institutional websites. Search the paper name and DOI and “pdf” in a search engine to see if any results show up.

If you have any friends who are students or work in a University, ask them to download the paper for you: all you need to do is send them the DOI, and they can check if their university has a subscription to the journal.

If you can’t find it online or don’t have contacts with a uni account, you should shoot a brief, polite email to the corresponding author of the paper, telling them that you are interested in their work and would love to read their paper, but do not have a subscription to the journal. If you are polite (and they don’t have an overflowing inbox!) they will almost certainly send you on a copy of their research.

You can sail the seas with a jolly-roger raised…

4. Understanding consensus in research

So you’ve read through the paper, have drawn some conclusions, and have had a look at some other papers that cite it.

The important thing to remember that science is based on consensus. Results should be replicable: that is, if someone else tries to recreate the study, they should get similar results. The paper should have passed rigorous peer review. Just because one person says something is so in a research paper, does not mean it is so: this does not discount or discard anecdotal reporting, interviews etc. This data is all extremely meaningful. However, it does mean that is is difficult to make sweeping generalisations or statements about systems based on a few data points.

Just because someone went to Harvard to study economics and says X is effective, does not make it so. Do other experts in their field agree? Has this been rigorously proven in research? Research papers or their results are not loaned legitimacy by their author’s accolades: they become legitimate through testing, questioning, and attempts at prodding holes in them. Again, this is not to say lived experience is invalid and doesn’t have a place in academic writing - rather to say a degree does not a font of irrefutable knowledge make.

5. Understanding bias, inequity, and power dynamics in research

It is very important, especially when research involves people, to remember that science and research both are human-made constructs, and so carry all of our biases, bigotry, and systemic issues that any other construction does.

I think it’s very important every time you read research that involves people, to consider:

- Are the demographics of the participants recorded? If not, why?

- What are the possible social, historical, or cultural contexts at play that are not recorded?

- What possible harm may be done by implementing the strategies or methods outlined in the paper, and who would that harm most effect?

A useful rule-of-thumb to keep in mind, which I learned from the book Data Feminism is that if discussions around demographics are left out, you can usually assume that the research is built for and about the dominant socioeconomic group by default. Do with that information what you will.

For example, when looking at papers regarding effective techniques for teaching coding, one of the first things on my mind is:

Will this facilitate an inclusive and accessible classroom, or will it perpetuate the existing inequalities we see? Will it continue to create barriers?

Who were the research subjects learning through this technique, and how do they reflect my classroom? Who might be left behind by this technique? Who might this technique negatively effect?

What are the likely harms? Who might be harmed? What are the risks? How do these balance the benefits?

For example, if a technique requires rapid transcription of code from my screen by students, that will disadvantage students with processing issues, dyslexia, or other learning differences and disabilities. I’m wholly uninterested in a technique that might make other student’s learning slightly more efficient, at the cost of accessibility to others. I want to do no harm, and if that means eschewing a new and fancy technique until there is better research on its effectivity, so be it.

Researching a specific topic

Instead of stumbling upon some research in the wild, lets say you have a specific topic you want to find out about, or a specific question you want answered. There are a few key principles to keep in mind.

- Research is built on consensus: it is often better to read multiple studies in a shallow way than one or a few deeply. This is where those reviews I mentioned earlier come in to play: someone has done all the hard work for you, and has gone through the literature on a specific topic, and has compared and contrasted results and conclusions!

- If you can’t find a review on the topic you’re interested in, create a spreadsheet or table with the following headings: Paper citation, Big main question, Key result/conclusion, Methods, Limitations, Strengths, Opinion. Under citation, paste the url or DOI of the paper so you can find it again. Following the article linked above on how to read a paper, fill in the other columns with brief single-sentence descriptors. The “Opinion” column is for your own reflections on the results - for example, thoughts on limitations of the work, how broadly or narrowly applicable it might be, whether it contradicts or agrees with other work in the field.

It’s useful to have a basic primer on statistics in order to be able to properly assess results. The Art of Statistics by David Spiegelhalter is a fantastic book that explains in accessible and entertaining language how to approach reporting of results; how statistics can be misleading, and how to be aware of some common logical fallacies when it comes to looking over numerical results. Data literacy is an ever-more important skillset in today’s world, both to be able to absorb information from research articles, but also to be able to spot misinformation. It’s well worth investing time in these skills.

Use a research-focused search engine like Google Scholar to quickly return academic articles, instead of wading through a mire of unrelated blog-posts. Search key terms instead of phrases, and use the “cited by” function (illustrated above) to find related articles to flesh out your mini-review.

It’s ok not to understand everything: this goes back to the very first point at the start of this post. How high are the stakes? You’re not an expert in the field, so give yourself some leniency, and the time to absorb new information. Do not be afraid to admit defeat and seek out experts if it is important! Also beware the Dunning-Kreuger effect and remain humble and realistic about your knowledge!

Build these skills over time. If you keep absorbing new research with a critical and skeptical mindset, you will become more efficient at quickly picking up on “bad research smells”: things that make your spidey-senses tingle when it comes to not disclosing all the limitations of a particular experiment, or not reporting the demographics of the research participants.

This has been a long and slightly rambling overview of different methods, approaches, and questions to ask when approaching research that is hopefully at least somewhat useful! Please leave a comment (see the Hypothesis sidebar) if you have any questions or comments!

Citation

@online{murphy_quinlan2025,

author = {Murphy Quinlan, Maeve},

title = {Is This Article Just Clickbait or Is It Good Science?},

date = {2025-05-21},

url = {https://murphyqm.github.io/posts/2025-05-21-reading-papers},

langid = {en}

}